Adding a processing step could reduce contamination in groundnut flour

By Allison Floyd

University of Georgia, Peanut & Mycotoxin Innovation Lab

Tiwonge Longwe already was interested in nutrition when her studies led her to the conclusion that improving food processing might give her the chance to impact the most people.

“As I was pursuing my undergraduate degree in Nutrition and Food Science, I developed keen interest in physico-chemistry of food and understanding the processing of food. With time, the interest grew stronger and I decided to major in Food Science and Technology,” said Longwe, a 24-year-old student supported by the Peanut & Mycotoxin Innovation Lab. She returned to the Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources in her home country of Malawi to pursue a master’s degree.

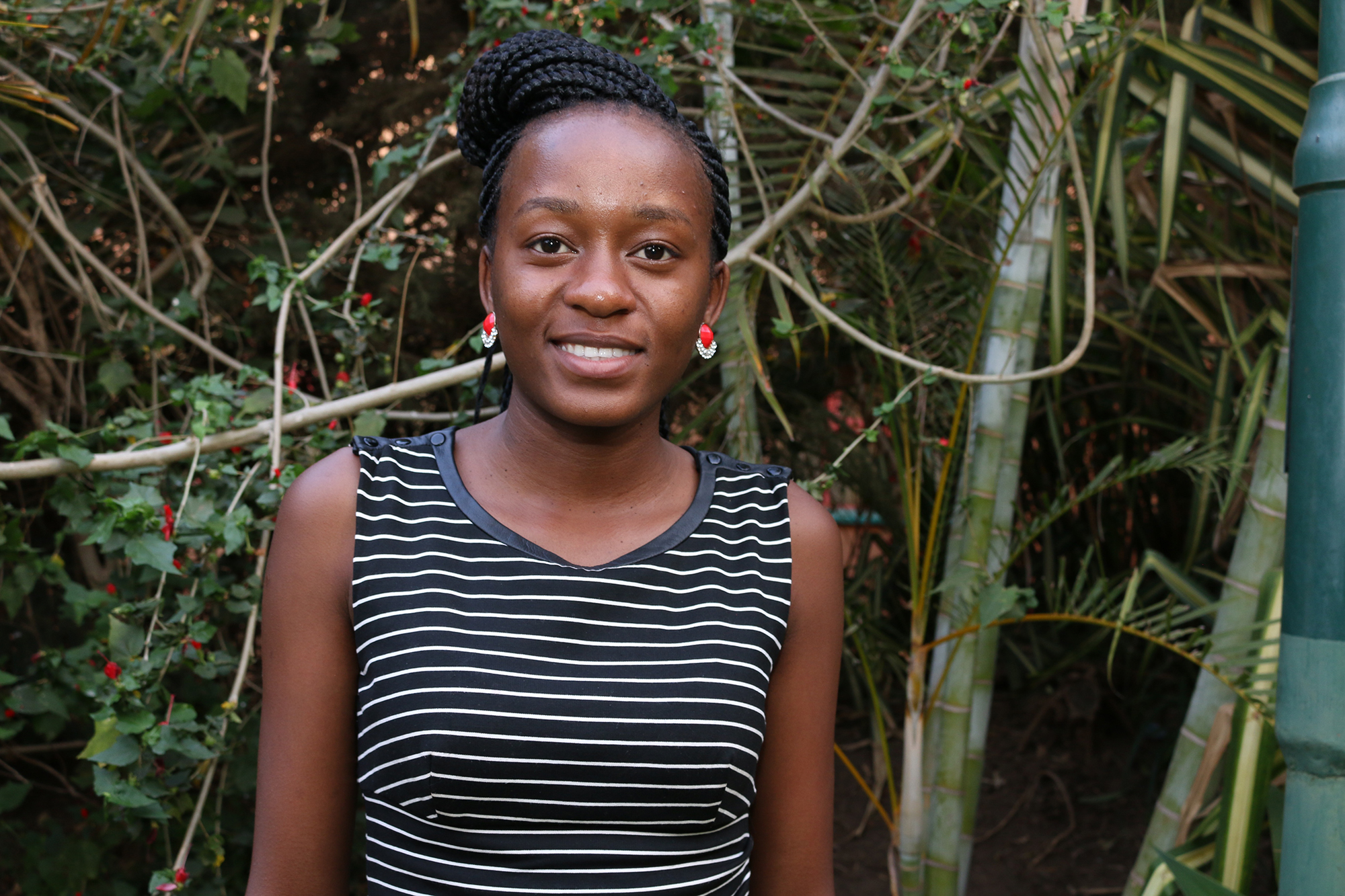

Tiwonge Longwe, a Food Science and Technology master's student at Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, researched whether adding a blanching step before making peanut flour would reduce the level of aflatoxin in the final product.

“My interest in groundnuts grew as I saw that groundnuts are one of the most grown crops in my country, but also the one that carries the most risk as regards to food safety. I thought I would make a contribution into changing the safety of groundnut flour for the consumers,” she said.

Peanuts and other crops, such as maize, are susceptible to the type of mold that produces aflatoxin, a carcinogenic substance that also is linked to childhood stunting and wasting. Peanut flour – or nsinjiro as it is known in Malawi – may contain particularly high levels of aflatoxin because discolored or moldy nuts that are unacceptable for other products are often used as a raw material and milling can lead to cross contamination and increase of aflatoxin in the final product.

Longwe’s research to gain a degree in Food Science and Technology explored the effects that blanching has on removing aflatoxin from contaminated peanuts – or groundnuts as they are called in most of Africa.

Researchers have worked for years to find interventions that minimize the risk of aflatoxin contamination during growing and storage.

But, Longwe wanted to explore whether blanching – a process that involves exposing raw groundnuts to a quick blast of dry heat to help remove the skin – could impact the amount of aflatoxin that winds up in the flour consumers eat. Making groundnut flour in Malawi doesn’t involve blanching, traditionally, so she asked whether adding that production step could reduce the amount of aflatoxin in the final product.

“Low quality nuts are milled into flour together with mould-infested and rotten ones. In trying to encourage processors to reduce the risk, blanching followed by sorting was suggested,” Longwe said. In her experiments, blanching the nuts and sorting out the ones with visible damage reduced aflatoxin to non-detectable levels.

Still, blanching the nuts has a tradeoff in quality, and Longwe wanted to see how the process affected cooking qualities and shelf-life of the flour.

Blanching reduced protein and fiber in the flour (found in the skins which had been removed), but didn’t change the way flour mixes or cooks in any way that would keep cooks from using flour from blanched nuts to make traditional dishes.

“Functionality wise, dry blanching coupled with sorting did not have significant effect on water absorption capacity, water holding capacity and foaming capacity,” she said. “Dry blanching, however, enhanced oil absorption capacity, water solubility index, and water absorption index and gelation temperature of full fat groundnut flour.”

Dry blanching also curtailed the growth of bacteria, yeast and moulds during storage. Blanching did, however, increase peroxide, free fatty acids, and malonaldehyde, evidence that the shelf life would be shortened due to oxidation, leading to rancidity.

“I expect people to adopt blanching coupled with sorting as it has been proven that it reduces aflatoxin contamination levels and it also causes non-significant changes in the functionality and would therefore not limit its use in food applications,” Longwe said. “I would also recommend that groundnut flour processors should not store their flour for more than three months as it would have had high levels of rancidity beyond three months.”

When she wraps up her master’s degree in late 2017, Longwe plans to go to work, then return to school at some point to pursue a doctorate. Perhaps she’ll have the chance to research some questions that her work brought to mind.

“Given another chance, I would repeat this research, but I would focus more on packaging materials used for groundnut flour, as packaging plays a big role in food preservation,” she said. “I would want to answer how each packaging material directly influences rate of fat deterioration and growth of microbes in order to make proper recommendations.” Improved packaging quality and techniques could reduce the negative impact of dry blanching on shelf life.

She’s enjoyed working in the lab, which gave her a sense of ownership in her research, and helping processors better understand how a simple, available technology like blanching can improve the safety of their groundnut flour.

“My favorite part of the research was the practicality of blanching as a method of reducing aflatoxin contamination in our groundnut products,” she said.

-Published July 31, 2017